Standing in a crowd in the starting chute, I waited for the gun signaling the beginning of the race. For the first time in my 10 years of distance running, I wasn’t sure if I would finish. This race was different than anything else I had attempted, and there was no way for me to replicate this race during training.

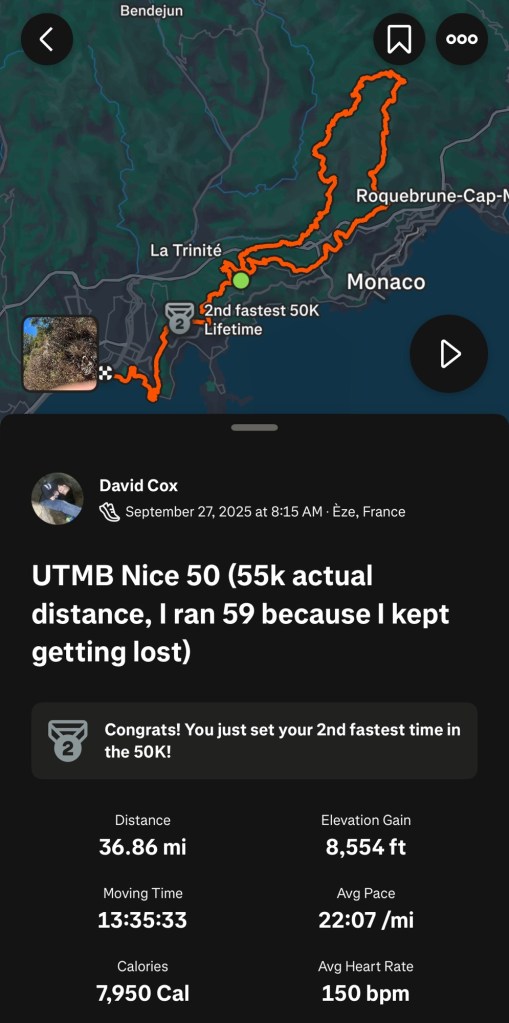

Several months ago, I chose to sign up for the UTMB Nice Côte d’Azur 50K trail ultramarathon. It was a way for me to celebrate my 50th birthday by doing something difficult but achievable for an aging endurance athlete. Officially, the course was 34 miles long with a total elevation gain of 7,100 feet. The longest race I had done in the past was the Quad Cities Marathon, which was 26.2 miles and had a total elevation gain of less than 500 feet. An extra 8 miles was one thing, but the difference in elevation gain was off the charts.

My training had gone mostly according to plan; my final long run was 31 miles and around a thousand feet of elevation gain. During that training run, I did something that caused me significant pain on the top of my left foot, which appeared to be a ligament issue. It wasn’t a huge injury, but it caused me to back off my training significantly in order to allow that foot to heal up as well as possible. I didn’t want to limp through 34 miles. I hoped that the drop off in running wouldn’t affect my ability to finish.

The start of the race was broken into five waves, each 15 minutes apart. With much of the race taking place on single-track trails, it was important to get the runners spread out as soon as possible, and the starting waves helped to space those runners. I was in the fourth of five waves. When it was our turn in the chute, the Race Director tried to keep us loose by playing dance music and giving us encouragement.

Our 15 minutes expired, and we were off. The first portion of the race was mostly uphill on an asphalt road through a pine forest. I was staying true to my plan—keeping my heart rate fairly low—walking the uphills and running the downhills and flats in an effort to maintain my energy for late in the race. Virtually everyone else around me was following the same strategy.

At the end of the first mile, we passed a large wooden sign that said “Parc Naturel Departmental De La Grande Corniche”. We were entering a park perched on the bluffs overlooking the Mediterranean. We would be running through that park for the next few miles. As we continued through the park, asphalt roads made way to gravel roads and finally to a rocky hiking path.

It didn’t take long to catch a glimpse of the Mediterranean, and soon we were treated to panoramic views of the coast. Early on, there were fantastic views of Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat, a wealthy residential development on a peninsula to the east of Nice. It is also the start of the 20K race that would start the next day.

The next several miles were breathtaking. The path followed the bluffs overlooking the Mediterranean. Every view was amazing as we looked over multiple settlements along the coast from Nice to Monaco. There were countless yachts and sailboats along the coast as well.

The path was mostly crushed rock and comfortable to run. A number of tunnels were also carved out along this path. I honestly can’t imagine a more ideal setting for the beginning of a race; this was why I signed up for this race; it was just beautiful.

The UTMB Nice 50K is divided into five sections. Four aid stations are spaced approximately 11 kilometers apart, and I arrived at the first aid station in less than an hour and a half. That was a little slower than I thought I would take, but I felt good. I grabbed a couple of sugary snacks to pump up my energy and moved on to the second section.

I was worried about the second section. It was about 12 kilometers long, but had a total of more than 2,500 feet of elevation gain. It was time to find out what my legs could take.

The trail changed as well; no longer were we running on wide paths on comfortable surfaces. We had switched to narrow, single-track paths with large rocks everywhere. The next eight kilometers to Col de Madone would have a fairly gradual increase of over 1,500 feet.

Over that stretch, I had kept a fairly good pace, keeping up with the runners ahead of me. My legs were starting to feel the burn a little, but I was feeling confident. Maybe this won’t be that bad.

Once we reached Col de Madone, an official with the race instructed people to prepare themselves for the most difficult climb in the race. We were at the base of Cime du Baudon, and we needed to climb 900 feet over less than a mile. Considering I had already climbed 1,500 feet over the last 5 miles, this was going to be a challenge.

This climb consisted of many parts where we had to use our hands to climb up on large rocks. There was also a lot of loose rock on the paths in this area, which made the footing tricky. This part of the race felt much more like an intense hike than a run. I had to take a lot of breaks to catch my breath, as did the other runners.

It became very clear to me at this point that my training in flat Iowa didn’t prepare me for this elevation change. As I neared the top, I was taking more frequent breaks, and my thighs were absolutely screaming at me to quit. I knew that at the peak, we would be nearly 4,000 feet above sea level, at the absolute highest point of the race, and we would be finishing at sea level. It becomes much more of a downhill race if I could just get to the top.

Nearly exhausted, I reached the top, and my Garmin told me that I had just completed a 52-minute mile. I can say without question that I hadn’t planned to take that long to climb Cime du Baudon, but as Mike Tyson once said, “Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.”

From the peak, the views were extraordinary. Not only were the multitude of peaks in the Maritime Alps visible, but also the Mediterranean Sea. Off in the distance, to my astonishment, I could see the runway at the Nice Airport, which was more than 10 miles away. My legs were spent, I was exhausted, but this was amazing.

The next mile was a reverse of the climb up to Cime du Baudon, with a similar grade going downhill. I spent the majority of my energy trying not to fall. I mostly used my hiking poles as stabilizers as I shuffled and slid down the loose rocks. Even though I was going downhill, I took 32 minutes to go the next mile because of how steep the terrain was.

The next aid station was just around the corner in Peille. I was looking forward to filling up my water and grabbing a few snacks. Running downhill through the cobblestone streets, I was feeling energized and encouraged to have reached the end of the second section of the race.

Those good feelings were quickly squashed when I realized I had completely run through the town and missed the aid station. I had to go back. I wasn’t sure if I had to check in at each aid station to make the race official, but I needed water anyway. I overshot the aid station by more than half a mile, and now I was going uphill, asking for directions to get to the aid station. The last thing I needed was more distance and more elevation change.

I got to the aid station and they seemed to be cleaning up, but they filled up my water gave me some snacks, and I was back out on the trail.

Over the next couple of sections of the race, I questioned whether I could finish the race. One thing became apparent to me: I wasn’t going to be able to run nearly as much as I had hoped. The paths were full of baseball-sized rocks, and every time that I started to get a little speed, I would land awkwardly on my foot. I just hadn’t trained for running on this type of surface, and it was punishing me.

In the middle of this, Jenn texted me, and I grabbed my phone to text her back, then immediately tripped over one of those rocks and fell hard. It was the first of four falls I took during this run. I cut my left knee this time, brushed it off, and kept going.

It was also very apparent that at this time, I was all alone. I texted Jenn that I was pretty sure that of the people still in the race, I was in last place. With the terrain and my lack of experience on this trail, I just couldn’t move fast enough without it being dangerous.

As I inched closer to the third aid station, I had a 600 to 700-foot climb, and my quads were on fire. On the downhills and flats, I felt fine, but every time I had to climb a hill, I questioned whether or not I would be able to continue. I took my time and took breaks when I needed to, and kept putting one foot in front of the other until I was at the top of the hill with just a quick couple of miles to the aid station.

At the aid station, I filled up my water and grabbed some snacks. Jenn sent me a text message saying that I had 4 hours until the cutoff at the next aid station. Until that text, I hadn’t even considered that I was close to being disqualified, but apparently, I only made the cut-off at the third aid station by a matter of a few minutes.

Hurriedly, I finished my snack and left, following a couple of women, who, after about a half mile, struggled to get down a steep slope into a dried-up creek bed. I saw this and knew I was going to need my hiking poles to get down, but realized that I didn’t have them; they were back at the aid station. So I had to return to the aid station to grab them.

For the second aid station in a row, I had to double back, each time it cost me a mile and probably at least 20 minutes. Now I knew I was in last place. That became apparent when, in a couple of miles, I started to hear noise behind me. It was the sweepers, cleaning up the course behind me. They came up behind me and told me that they were closing the course, and at first, I thought they were going to disqualify me.

They asked me if I could make it to the next aid station, and I told them I had plenty of time and I wasn’t worried about it. I was, however, annoyed by their constant presence behind me. I just wanted them to leave me alone, and they were always right behind me.

It was about this time that the 50K route merged with the 100 Mile route and the 100K route. I think the sweepers no longer were closing the course, since the other runners needed to use the course, but they continued to follow right behind me, which was beginning to get on my nerves.

I got a text message from Jenn, who was following my progress on the Live Trail app, saying that I had one big hill left. Over the next two miles, I was going to have to climb about 700 feet. However, after that, there was only about another 300 feet of climb for the remaining nine miles. I just needed to get up this last hill. With the sweepers on my tail, I continued to put one foot in front of the other, gasping for air, and my thighs on fire. Finally, I made it to the top of the hill.

I was at Plateau de la Justice, just two miles from the final aid station and around nine miles from the finish. At that moment, I realized that, barring an injury, I was going to finish. The only time I questioned whether I could continue was going uphill, and except for a little bit of elevation gain, it was all flat and downhill for the rest of the race. It was an emotional moment knowing that I was going to finish after spending the better part of the last few hours questioning whether I could.

I made it to the aid station and filled my water for the final time. I choked down some cookies, hoping the sugar would give me a boost of energy, and got back to the race.

Once I hit the aid station, I was no longer alone on the course. Somehow, I managed to catch and pass some 50K runners, and an increasing number of 100 milers were coming up from behind us.

A short while from the aid station, the trail passed through Parc du Viniagrier. This section was a steep downhill single-person switchback trail, which was full of stones. By this time, running on these stones was tearing up my feet, my whole body ached, and my legs were almost completely spent. It was also getting darker by the minute as it was now dusk.

This was a highly technical section, and I was exhausted. I needed to stay focused so I wouldn’t hurt myself. Then, while in a fairly steep section, I caught a toe on a rock and fell face-first down the hill. I managed to get my hand in front of my face and stopped myself from taking a rock to the forehead. I felt a sharp pain in my hand and got up. There was blood dripping down my hand.

I decided to continue on and hoped that it would stop bleeding on its own, which it did. All of the aches and pains were starting to multiply, and I was ready to be done. As I pushed through the natural area at Mt Boron, I was treated to an amazing view of Nice at night from about 600 feet above the city.

Mt Boron had the last natural trails left in the route, and once I climbed down an incredibly steep and long set of stairs, I was at sea level. I had just a little over two miles to go along the coast and the Marina.

My pace increased, running around the Marina by streetlight, through pedestrians. Some were unaware of what was happening, and others were cheering us on. Finally, I turned along the promenade and headed into the finishers’ chute.

I crossed the finish line in 13 hours and 40 minutes, just 20 minutes before the 14-hour cutoff. My goal was to finish in 10 hours. I didn’t care, though; I was just happy to have finished.

It was the greatest physical challenge I had ever faced, and just finishing was enough for me. I was on the edge of exhaustion so many times and just kept putting one foot in front of the other. It’s a reminder of the power of perseverance.

I spent the next several days physically recovering from the race. It took a day to get my appetite back, two for my energy to return, and over a week before I could walk without limping. But within a couple of weeks, I was already trying to find another UTMB World Series race to participate in.

UTMB World Series races are an amazing combination of extreme challenge and extreme beauty. They take place in some of the most beautiful parks and natural areas throughout the world. It’s worth every blister, scrape, and cut. As sadistic as it sounds, I can’t wait to do another.

Great article and congratulations on the run!!

LikeLike